Indigenous Knowledge for Food Sovereignty: A Pathway to Resilience

By Temidayo Paul Aturu

Khadija is a widowed farmer in Sub-Saharan Africa. She is making her living for herself and her two kids as a subsistence farmer, taking the occasional odd job. Her maize fields look wonderful this time of year, but she knows that if and when a drought comes, most of her hard labour could all but be in vain.

Luckily, she is now in the hands of capable agroecologists who help her grow using methods that give her hope. She will return to her origins and begin to farm again like her grandparents did before her, using traditional farming methods, but this time based on scientific studies that help her understand why she does what she does, and how it works in principles and techniques.

For centuries, farming was based on simple, sustainable practices that worked in harmony with nature. Indigenous communities relied on traditional knowledge to grow food while maintaining soil health, biodiversity, and ecological balance. Their methods were adapted to local environments, using locally hardened species, ensuring long-term food security. We sometimes refer to them as the lost crops of Africa.

In the 20th century, industrial agriculture replaced these practices with large-scale monocropping, heavy machinery, and chemical inputs. Special hybrid varieties of staple crops and vegetables were proliferated that required these inputs. The goal was to increase productivity, but this came at the cost of sustainability. Soil degradation, loss of biodiversity, and environmental harm became widespread.

Today, with growing challenges like climate change, food insecurity, and ecosystem collapse, there is a renewed interest in returning to the olden ways, to indigenous farming wisdom. This is humanity's lesson in humility that offers resilience, sustainability, and food sovereignty throughout the world's farming communities.

Indigenous Farming Systems: Lessons in Sustainability

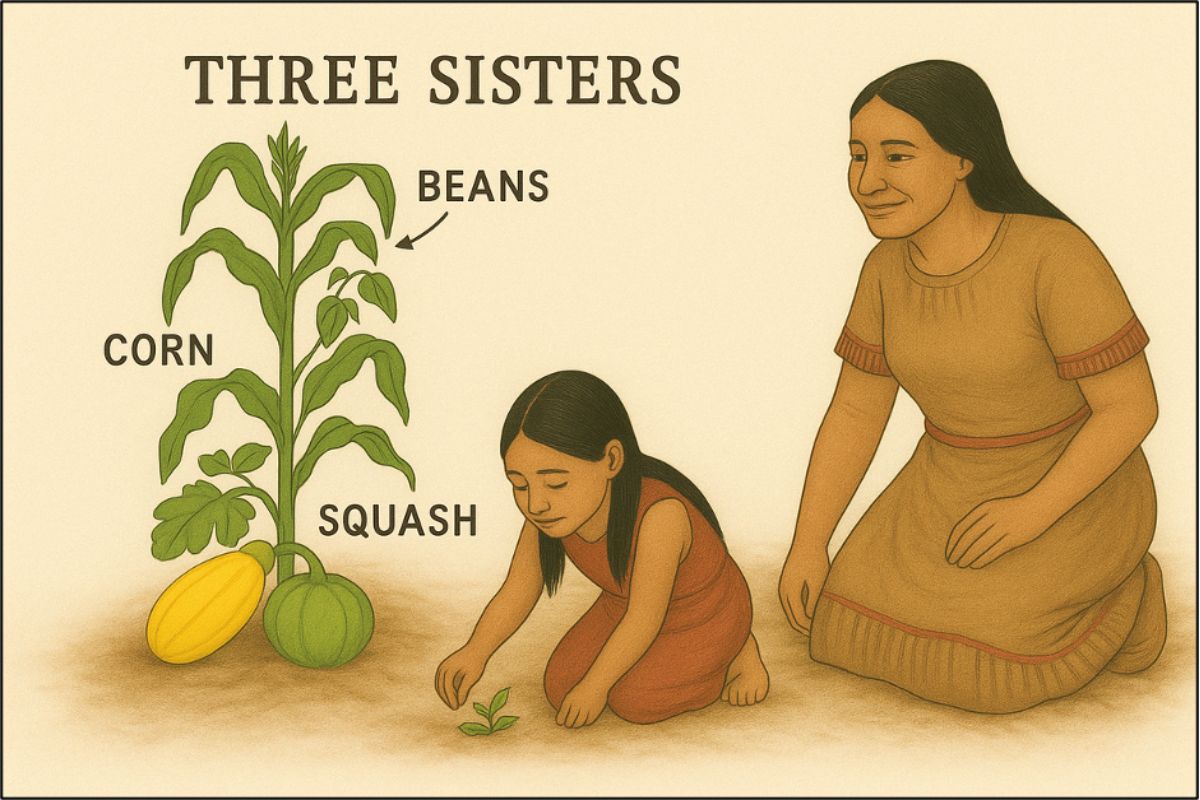

One shining example of Indigenous farming knowledge is the Three Sisters, which showcases a model of traditional heritage and now fosters interdependence for centuries after it was first used. The Three Sisters—corn, beans, and squash—are a well-known Indigenous farming system from North America, developed by the Haudenosaunee (Iroquois) and other Native communities. It is now spreading all over the world, gaining ground in depleted soils through human perseverance. These three sisters grow together and support each other like a family.

- The taller sister, Corn, provides a natural structure for beans to climb.

- The younger, chubby sister, the Bean, climbs her tall sister's stalky legs, and in return, fixes nitrogen with her feet solidly planted in the ground, enriching the soil with vital nutrients in the form of nitrogen—feeding all three sisters.

- The lazy Squash sister spreads herself across the ground, casting a shadow with her soft leaves, keeping the surface of the soil cool, retaining moisture, suppressing the evil weeds, and preventing soil erosion beneath their feet, the place they call home.

This system maximizes land use by growing in 3 layers within the same square feet area, providing a crop for a whole meal to be cooked in a healthy kitchen. It improves soil fertility for next year and removes the need for modern chemical inputs. As such, outside of its practical benefits, the Three Sisters also hold cultural and spiritual significance, representing a deep connection to the Earth and embedded in the nighttime fairy tales in human lullabies or around the campfire.

In Mesoamerica, the milpa system is similar to the Three Sisters but includes additional crops like chili peppers, tomatoes, and root vegetables. The family keeps growing. Farmers rotate crops to maintain soil fertility naturally, avoiding the need for alien synthetic fertilizers. This ancient agroecological system supports diversity in diets and is the starter for building resilient ecosystems with a human-centered approach.

As our 76-year-old innovative farmers in Ghana tell us, “If we had known we could grow more than one crop in the same soil, we would always have done so. If one fails, the others will succeed. And together, they are stronger.”

Conclusion: The Future of Food Lies in the Past

Indigenous and traditional agroecological farming systems hold time-tested solutions to modern food security and climate challenges. Rooted in truly sustainable practices like crop diversity, agroforestry, and soil regeneration, these methods prioritize harmony with nature rather than exploitation. In contrast to industrial agriculture, which depletes resources and worsens climate change, Indigenous knowledge offers resilient, low-input alternatives that are easier to work with than machinery and machines, while also ensuring better food security, protecting ecosystems, and increasing biodiversity. By supporting and reviving these ancient practices in our own gardens, we can build an understanding of a more sustainable and equitable food future for the whole planet.

This article was produced in collaboration with eGro, a Founding partner to Fellow Future dedicated to advancing sustainable solutions in agroforestry and beyond.